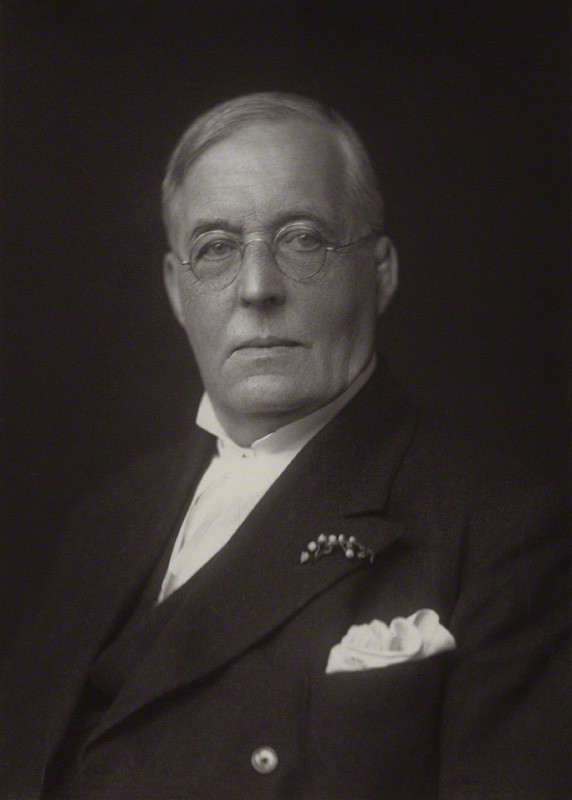

Apart from Edgar Allan Poe, there was no

bigger name in horror fiction during the nineteenth century than one Bram

Stoker. He was born in Dublin, Ireland and the third of seven children. He

suffered from an unknown illness and spent most his days bedridden until he

recovered at the age of seven. Later he attended Trinity College, Dublin where he studied mathematics. Stoker became

the personal assistant to the popular stage actor Henry Irving. He is mentioned

by one of the characters in “The Squaw.”

Bram Stoker started his literary career by writing short stories. “The Crystal Cup” was his first. It

was published in 1872 when Stoker was twenty-five. Rats soon became his animal

of choice in a number of his tales, including, of course, “The Burial of the

Rats” (1896) and his best ghost story, “The Judge’s House” (1891).

He also used cats (black

ones) to weave the most fiendish cat horror tale since Edgar Allan Poe’s “The

Black Cat” (1843) published 50 years earlier. “The Squaw” will never be

mistaken for a warm holiday story, yet it was published in the December 2nd

Christmas issue of The Illustrated

Sporting of Dramatic News magazine, titled “Holly Leaves” on its cover.

In 1893, Stoker took a

break from writing Dracula to publish

“The Squaw.” He viewed the story as being that important. It includes an American

with a thick Southern accent that can be overbearing at times.

“The Squaw” was first

published in book form by Stoker’s wife, Florence, during 1914. This was two

years after Stoker’s death. The anthology titled Dracula’s Guest and Other Stories further contained the first

publication of “Dracula’s Guest,” a segment cut from the Dracula novel due to length.

Given the excellent

writing, character generation and shocking ending, “The Squaw” is one of Bram

Stoker’s greatest horror short stories.

The Squaw

1893

|

N

|

URNBERG AT THE time was not so much exploited

as it has been since then. Irving had not been playing Faust, and the very name of the old town was hardly known to the great bulk of the

travelling public.

My wife and I being in

the second week of our honeymoon, naturally wanted someone else to join our

party, so that when the cheery stranger, Elias P. Hutcheson, hailing from

Isthmian City, Bleeding Gulch, Maple Tree County, Neb. turned up at the station at Frankfort, and casually remarked that he was going

on to see the most all-fired old Methuselah of a town in Yurrup, and that he guessed that so much travelling alone was

enough to send an intelligent, active citizen into the melancholy ward of a

daft house, we took the pretty broad hint and suggested that we should join

forces.

We found, on comparing

notes afterwards, that we had each intended to speak with some diffidence or

hesitation so as not to appear too eager, such not being a good compliment to

the success of our married life; but the effect was entirely marred by our both

beginning to speak at the same instant—stopping simultaneously and then going

on together again.

Anyhow, no matter how,

it was done; and Elias P. Hutcheson became one of our party. Straightway Amelia

and I found the pleasant benefit; instead of quarrelling, as we had been doing,

we found that the restraining influence of a third party was such that we now

took every opportunity of spooning in odd corners. Amelia declares that ever

since she has, as the result of that experience, advised all her friends to

take a friend on the honeymoon. Well, we “did” Nurnberg together, and much

enjoyed the racy remarks of our Transatlantic friend, who, from his quaint

speech and his wonderful stock of adventures, might have stepped out of a

novel. We kept for the last object of interest in the city to be visited the

Burg, and on the day appointed for the visit strolled round the outer wall of

the city by the eastern side.

The Burg is seated on a

rock dominating the town and an immensely deep fosse guards it on the northern

side. Nurnberg has been happy in that it was never sacked; had it been it would certainly not be so spick and span perfect as it is at

present. The ditch has not been used for centuries, and now its base is spread

with teagardens and orchards, of which some of the trees are of quite

respectable growth.

As we wandered round

the wall, dawdling in the hot July sunshine, we often paused to admire the

views spread before us, and in especial the great plain covered with towns and

villages and bounded with a blue line of hills, like a landscape of Claude

Lorraine.

From this we always

turned with new delight to the city itself, with its myriad of quaint old

gables and acre-wide red roofs dotted with dormer windows, tier upon tier. A

little to our right rose the towers of the Burg, and nearer still, standing

grim, the Torture Tower, which was, and is, perhaps, the most interesting place in the city. For

centuries the tradition of the Iron Virgin of Nurnberg has been handed down as an instance of the horrors of cruelty of which man is

capable; we had long looked forward to seeing it; and here at last was its

home.

In one of our pauses we

leaned over the wall of the moat and looked down. The garden seemed quite fifty

or sixty feet below us, and the sun pouring into it with an intense, moveless

heat like that of an oven. Beyond rose the grey, grim wall seemingly of endless

height, and losing itself right and left in the angles of bastion and counterscarp. Trees and bushes crowned the wall, and above again towered the lofty houses on

whose massive beauty Time has only set the hand of approval. The sun was hot

and we were lazy; time was our own, and we lingered, leaning on the wall. Just

below us was a pretty sight—a great black cat lying stretched in the sun,

whilst round her gamboled prettily a tiny black kitten. The mother would wave

her tail for the kitten to play with, or would raise her feet and push away the

little one as an encouragement to further play. They were just at the foot of

the wall, and Elias P. Hutcheson, in order to help the play, stooped and took

from the walk a moderate sized pebble.

“See!” he said, “I will

drop it near the kitten, and they will both wonder where it came from.”

“Oh, be careful,” said

my wife; “you might hit the dear little thing!”

“Not me, ma’am,” said

Elias P. “Why, I’m as tender as a Maine cherry-tree. Lor, bless ye. I wouldn’t

hurt the poor pooty little critter more’n I’d scalp a baby. An’ you may bet

your variegated socks on that! See, I’ll drop it fur away on the outside so’s

not to go near her!”

Thus saying, he leaned

over and held his arm out at full length and dropped the stone. It may be that

there is some attractive force which draws lesser matters to greater; or more

probably that the wall was not plump but sloped to its base—we not noticing the

inclination from above; but the stone fell with a sickening thud that came up

to us through the hot air, right on the kitten’s head, and shattered out its

little brains then and there. The black cat cast a swift upward glance, and we

saw her eyes like green fire fixed an instant on Elias P. Hutcheson; and then

her attention was given to the kitten, which lay still with just a quiver of

her tiny limbs, whilst a thin red stream trickled from a gaping wound.

With a muffled cry,

such as a human being might give, she bent over the kitten licking its wounds

and moaning. Suddenly she seemed to realize that it was dead, and again threw

her eyes up at us. I shall never forget the sight, for she looked the perfect

incarnation of hate. Her green eyes blazed with lurid fire, and the white,

sharp teeth seemed to almost shine through the blood which dabbled her mouth

and whiskers.

She gnashed her teeth,

and her claws stood out stark and at full length on every paw. Then she made a

wild rush up the wall as if to reach us, but when the momentum ended fell back,

and further added to her horrible appearance for she fell on the kitten, and

rose with her black fur smeared with its brains and blood. Amelia turned quite

faint, and I had to lift her back from the wall.

There was a seat close

by in shade of a spreading plane-tree, and here I placed her whilst she

composed herself. Then I went back to Hutcheson, who stood without moving,

looking down on the angry cat below.

As I joined him, he

said:

“Wall, I guess that air

the savagest beast I ever see—’cept once when an Apache squaw had an edge on a half-breed what they nicknamed ‘Splinters’ ‘cos of the way he

fixed up her papoose which he stole on a raid just to show that he appreciated the way they had

given his mother the fire torture. She got that kinder look so set on her face

that it jest seemed to grow there. She followed Splinters mor’n three year till

at last the braves got him and handed him over to her. They did say that no

man, white or Injun, had ever been so long a-dying under the tortures of the

Apaches. The only time I ever see her smile was when I wiped her out. I kem on

the camp just in time to see Splinters pass in his checks, and he wasn’t sorry

to go either. He was a hard citizen, and though I never could shake with him

after that papoose business—for it was bitter bad, and he should have been a

white man, for he looked like one—I see he had got paid out in full. Durn me,

but I took a piece of his hide from one of his skinnin’ posts an’ had it made

into a pocketbook. It’s here now!” and he slapped the breast pocket of his

coat.

Whilst he was speaking

the cat was continuing her frantic efforts to get up the wall. She would take a

run back and then charge up, sometimes reaching an incredible height. She did

not seem to mind the heavy fall which she got each time but started with

renewed vigor; and at every tumble her appearance became more horrible.

Hutcheson was a kind-hearted man—my wife and I had both noticed little acts of

kindness to animals as well as to persons—and he seemed concerned at the state

of fury to which the cat had wrought herself.

“Wall, now!” he said, “I

du declare that that poor critter seems quite desperate. There! there! poor

thing, it was all an accident—though that won’t bring back your little one to

you. Say! I wouldn’t have had such a thing happen for a thousand! Just shows

what a clumsy fool of a man can do when he tries to play! Seems I’m too darned

slipper-handed to even play with a cat. Say Colonel!” it was a pleasant way he

had to bestow titles freely—“I hope your wife don’t hold no grudge against me

on account of this unpleasantness? Why, I wouldn’t have had it occur on no

account.”

He came over to Amelia

and apologized profusely, and she with her usual kindness of heart hastened to

assure him that she quite understood that it was an accident. Then we all went

again to the wall and looked over.

The cat missing

Hutcheson’s face had drawn back across the moat, and was sitting on her

haunches as though ready to spring. Indeed, the very instant she saw him she

did spring, and with a blind unreasoning fury, which would have been grotesque,

only that it was so frightfully real. She did not try to run up the wall, but

simply launched herself at him as though hate and fury could lend her wings to

pass straight through the great distance between them. Amelia, womanlike, got quite

concerned, and said to Elias P. in a warning voice:

“Oh! you must be very

careful. That animal would try to kill you if she were here; her eyes look like

positive murder.”

He laughed out

jovially. “Excuse me, ma’am,” he said, “but I can’t help laughin’. Fancy a man

that has fought grizzlies an’ Injuns bein’ careful of bein’ murdered by a cat!”

When the cat heard him

laugh, her whole demeanor seemed to change. She no longer tried to jump or run

up the wall, but went quietly over, and sitting again beside the dead kitten

began to lick and fondle it as though it were alive.

“See!” said I, “the

effect of a really strong man. Even that animal in the midst of her fury

recognizes the voice of a master, and bows to him!”

“Like a squaw!” was the

only comment of Elias P. Hutcheson, as we moved on our way round the city

fosse.

Every now and then we

looked over the wall and each time saw the cat following us. At first she had

kept going back to the dead kitten, and then as the distance grew greater took

it in her mouth and so followed. After a while, however, she abandoned this,

for we saw her following all alone; she had evidently hidden the body

somewhere. Amelia’s alarm grew at the cat’s persistence, and more than once she

repeated her warning; but the American always laughed with amusement, till

finally, seeing that she was beginning to be worried, he said:

“I say, ma’am, you

needn’t be skeered over that cat. I go heeled, I du!” Here he slapped his

pistol pocket at the back of his lumbar region. “Why sooner’n have you worried,

I’ll shoot the critter, right here, an’ risk the police interferin’ with a

citizen of the United States for carryin’ arms contrairy to reg’lations!” As he

spoke he looked over the wall, but the cat on seeing him, retreated, with a

growl, into a bed of tall flowers, and was hidden. He went on: “Blest if that

ar critter ain’t got more sense of what’s good for her than most Christians. I

guess we’ve seen the last of her! You bet, she’ll go back now to that busted

kitten and have a private funeral of it, all to herself!”

Amelia did not like to

say more, lest he might, in mistaken kindness to her, fulfil his threat of

shooting the cat: and so we went on and crossed the little wooden bridge

leading to the gateway whence ran the steep paved roadway between the Burg and

the pentagonal Torture Tower. As we crossed the bridge we saw the cat again

down below us. When she saw us her fury seemed to return, and she made frantic

efforts to get up the steep wall. Hutcheson laughed as he looked down at her, and

said:

“Goodbye, old girl.

Sorry I injured your feelin’s, but you’ll get over it in time! So long!” And

then we passed through the long, dim archway and came to the gate of the Burg.

When we came out again

after our survey of this most beautiful old place which not even the

well-intentioned efforts of the Gothic restorers of forty years ago have been

able to spoil—though their restoration was then glaring white—we seemed to have

quite forgotten the unpleasant episode of the morning. The old lime tree with its

great trunk gnarled with the passing of nearly nine centuries, the deep well

cut through the heart of the rock by those captives of old, and the lovely view

from the city wall whence we heard, spread over almost a full quarter of an

hour, the multitudinous chimes of the city, had all helped to wipe out from our

minds the incident of the slain kitten.

We were the only

visitors who had entered the Torture Tower that morning—so at least said the

old custodian—and as we had the place all to ourselves were able to make a

minute and more satisfactory survey than would have otherwise been possible.

The custodian, looking to us as the sole source of his gains for the day, was

willing to meet our wishes in any way. The Torture Tower is truly a grim place,

even now when many thousands of visitors have sent a stream of life, and the

joy that follows life, into the place; but at the time I mention it wore its

grimmest and most gruesome aspect. The dust of ages seemed to have settled on

it, and the darkness and the horror of its memories seem to have become

sentient in a way that would have satisfied the Pantheistic souls of Philo or Spinoza.

The lower chamber where

we entered was seemingly, in its normal state, filled with incarnate darkness;

even the hot sunlight streaming in through the door seemed to be lost in the

vast thickness of the walls, and only showed the masonry rough as when the

builder’s scaffolding had come down, but coated with dust and marked here and

there with patches of dark stain which, if walls could speak, could have given

their own dread memories of fear and pain. We were glad to pass up the dusty

wooden staircase, the custodian leaving the outer door open to light us

somewhat on our way; for to our eyes the one long-wick’d, evil-smelling candle

stuck in a sconce on the wall gave an inadequate light.

When we came up through

the open trap in the corner of the chamber overhead, Amelia held on to me so

tightly that I could actually feel her heart beat. I must say for my own part

that I was not surprised at her fear, for this room was even more gruesome than

that below. Here there was certainly more light, but only just sufficient to

realize the horrible surroundings of the place. The builders of the tower had

evidently intended that only they who should gain the top should have any of

the joys of light and prospect. There, as we had noticed from below, were

ranges of windows, albeit of mediaeval smallness, but elsewhere in the tower

were only a very few narrow slits such as were habitual in places of mediaeval

defense.

A few of these only lit

the chamber, and these so high up in the wall that from no part could the sky

be seen through the thickness of the walls. In racks, and leaning in disorder

against the walls, were a number of headsmen’s swords, great double-handed

weapons with broad blade and keen edge. Hard by were several blocks whereon the

necks of the victims had lain, with here and there deep notches where the steel

had bitten through the guard of flesh and shored into the wood.

Round the chamber,

placed in all sorts of irregular ways, were many implements of torture which

made one’s heart ache to see—chairs full of spikes which gave instant and

excruciating pain; chairs and couches with dull knobs whose torture was

seemingly less, but which, though slower, were equally efficacious; racks,

belts, boots, gloves, collars, all made for compressing at will; steel baskets

in which the head could be slowly crushed into a pulp if necessary; watchmen’s

hooks with long handle and knife that cut at resistance—this a specialty of the

old Nurnberg police system; and many, many other devices for man’s injury to

man.

Amelia grew quite pale

with the horror of the things, but fortunately did not faint, for being a

little overcome she sat down on a torture chair, but jumped up again with a

shriek, all tendency to faint gone. We both pretended that it was the injury

done to her dress by the dust of the chair, and the rusty spikes which had

upset her, and Mr. Hutcheson acquiesced in accepting the explanation with a

kind-hearted laugh.

But the central object

in the whole of this chamber of horrors was the engine known as the Iron

Virgin, which stood near the center of the room. It was a rudely-shaped figure

of a woman, something of the bell order, or, to make a closer comparison, of

the figure of Mrs. Noah in the children’s Ark, but without that slimness of

waist and perfect rondeur of hip which marks the aesthetic

type of the Noah family.[15]

One would hardly have recognized it as intended for a human figure at all had

not the founder shaped on the forehead a rude semblance of a woman’s face. This

machine was coated with rust without, and covered with dust; a rope was

fastened to a ring in the front of the figure, about where the waist should

have been, and was drawn through a pulley, fastened on the wooden pillar which

sustained the flooring above.

The custodian pulling

this rope showed that a section of the front was hinged like a door at one

side; we then saw that the engine was of considerable thickness, leaving just

room enough inside for a man to be placed. The door was of equal thickness and

of great weight, for it took the custodian all his strength, aided though he

was by the contrivance of the pulley, to open it. This weight was partly due to

the fact that the door was of manifest purpose hung so as to throw its weight

downwards, so that it might shut of its own accord when the strain was

released.

The inside was

honeycombed with rust—nay more, the rust alone that comes through time would

hardly have eaten so deep into the iron walls; the rust of the cruel stains was

deep indeed! It was only, however, when we came to look at the inside of the

door that the diabolical intention was manifest to the full. Here were several

long spikes, square and massive, broad at the base and sharp at the points,

placed in such a position that when the door should close the upper ones would

pierce the eyes of the victim, and the lower ones his heart and vitals.

The sight was too much

for poor Amelia, and this time she fainted dead off, and I had to carry her

down the stairs, and place her on a bench outside till she recovered. That she

felt it to the quick was afterwards shown by the fact that my eldest son bears

to this day a rude birthmark on his breast, which has, by family consent, been

accepted as representing the Nurnberg Virgin.

When we got back to the

chamber we found Hutcheson still opposite the Iron Virgin; he had been

evidently philosophizing, and now gave us the benefit of his thought in the

shape of a sort of exordium.

“Wall, I guess I’ve

been learnin’ somethin’ here while madam has been gettin’ over her faint. ‘Pears

to me that we’re a long way behind the times on our side of the big drink. We uster think out on the plains that the Injun could give us points in tryin’

to make a man uncomfortable; but I guess your old mediaeval law-and-order party

could raise him every time. Splinters was pretty good in his bluff on the

squaw, but this here young miss held a straight flush all high on him. The

points of them spikes air sharp enough still, though even the edges air eaten

out by what uster be on them. It’d be a good thing for our Indian section to

get some specimens of this here play-toy to send round to the Reservations jest to knock the stuffin’ out of the bucks, and the squaws too, by showing

them as how old civilization lays over them at their best. Guess but I’ll get

in that box a minute jest to see how it feels!”

“Oh no! no!” said

Amelia. “It is too terrible!”

“Guess, ma’am, nothin’s

too terrible to the explorin’ mind. I’ve been in some queer places in my time.

Spent a night inside a dead horse while a prairie fire swept over me in Montana

Territory—an’ another time slept inside a dead buffler when the Comanches]

was on the war path an’ I didn’t keer to leave my kyard on them. I’ve been two

days in a caved-in tunnel in the Billy Broncho gold mine in New Mexico, an’ was

one of the four shut up for three parts of a day in the caisson what slid over

on her side when we was settin’ the foundations of the Buffalo Bridge. I’ve not

funked an odd experience yet, an’ I don’t propose to begin now!”

We saw that he was set

on the experiment, so I said: “Well, hurry up, old man, and get through it

quick!”

“All right, General,”

said he, “but I calculate we ain’t quite ready yet. The gentlemen, my

predecessors, what stood in that thar canister, didn’t volunteer for the

office—not much! And I guess there was some ornamental tyin’ up before the big

stroke was made. I want to go into this thing fair and square, so I must get

fixed up proper first. I dare say this old galoot can rise some string and tie

me up accordin’ to sample?”

This was said

interrogatively to the old custodian, but the latter, who understood the drift

of his speech, though perhaps not appreciating to the full the niceties of

dialect and imagery, shook his head. His protest was, however, only formal and

made to be overcome.

The American thrust a

gold piece into his hand, saying: “Take it, pard! it’s your pot; and don’t be

skeer’d. This ain’t no necktie party that you’re asked to assist in!”

He produced some thin

frayed rope and proceeded to bind our companion with sufficient strictness for

the purpose. When the upper part of his body was bound, Hutcheson said:

“Hold on a moment,

Judge. Guess I’m too heavy for you to tote into the canister. You jest let me

walk in, and then you can wash up regardin’ my legs!”

Whilst speaking he had

backed himself into the opening which was just enough to hold him. It was a

close fit and no mistake. Amelia looked on with fear in her eyes, but she

evidently did not like to say anything. Then the custodian completed his task

by tying the American’s feet together so that he was now absolutely helpless

and fixed in his voluntary prison. He seemed to really enjoy it, and the

incipient smile which was habitual to his face blossomed into actuality as he

said:

“Guess this here Eve was made out of the rib of a dwarf! There ain’t much room for a full-grown

citizen of the United States to hustle. We uster make our coffins more roomier

in Idaho territory. Now, Judge, you jest begin to let this door down, slow, on

to me. I want to feel the same pleasure as the other jays had when those spikes

began to move toward their eyes!”

“Oh no! no! no!” broke

in Amelia hysterically. “It is too terrible! I can’t bear to see it!—I can’t! I

can’t!”

But the American was

obdurate. “Say, Colonel,” said he, “why not take Madame for a little promenade?

I wouldn’t hurt her feelin’s for the world; but now that I am here, havin’ kem

eight thousand miles, wouldn’t it be too hard to give up the very experience I’ve

been pinin’ an’ pantin’ fur? A man can’t get to feel like canned goods every

time! Me and the Judge here’ll fix up this thing in no time, an’ then you’ll

come back, an’ we’ll all laugh together!”

Once more the

resolution that is born of curiosity triumphed, and Amelia stayed holding tight

to my arm and shivering whilst the custodian began to slacken slowly inch by

inch the rope that held back the iron door. Hutcheson’s face was positively

radiant as his eyes followed the first movement of the spikes.

“Wall!” he said, “I

guess I’ve not had enjoyment like this since I left Noo York. Bar a scrap with

a French sailor at Wapping—an’ that warn’t much of a picnic neither—I’ve not

had a show fur real pleasure in this dod-rotted Continent, where there ain’t no

b’ars nor no Injuns, an’ wheer nary man goes heeled. Slow there, Judge! Don’t

you rush this business! I want a show for my money this game—I du!”

The custodian must have

had in him some of the blood of his predecessors in that ghastly tower, for he

worked the engine with a deliberate and excruciating slowness which after five

minutes, in which the outer edge of the door had not moved half as many inches,

began to overcome Amelia.

I saw her lips whiten,

and felt her hold upon my arm relax. I looked around an instant for a place

whereon to lay her, and when I looked at her again found that her eye had

become fixed on the side of the Virgin. Following its direction I saw the black

cat crouching out of sight. Her green eyes shone like danger lamps in the gloom

of the place, and their color was heightened by the blood which still smeared her

coat and reddened her mouth.

I cried out: “The cat!

look out for the cat!” for even then she sprang out before the engine. At this

moment she looked like a triumphant demon. Her eyes blazed with ferocity, her

hair bristled out till she seemed twice her normal size, and her tail lashed

about as does a tiger’s when the quarry is before it.

Elias P. Hutcheson when

he saw her was amused, and his eyes positively sparkled with fun as he said: “Darned

if the squaw hain’t got on all her war paint! Jest give her a shove off if she

comes any of her tricks on me, for I’m so fixed everlastingly by the boss, that

durn my skin if I can keep my eyes from her if she wants them! Easy there,

Judge! don’t you slack that ar rope or I’m euchered!”

At this moment Amelia

completed her faint, and I had to clutch hold of her round the waist or she

would have fallen to the floor. Whilst attending to her I saw the black cat

crouching for a spring, and jumped up to turn the creature out.

But at that instant,

with a sort of hellish scream, she hurled herself, not as we expected at

Hutcheson, but straight at the face of the custodian. Her claws seemed to be

tearing wildly as one sees in the Chinese drawings of the dragon rampant, and

as I looked I saw one of them light on the poor man’s eye, and actually tear

through it and down his cheek, leaving a wide band of red where the blood

seemed to spurt from every vein.

With a yell of sheer

terror which came quicker than even his sense of pain, the man leaped back,

dropping as he did so the rope which held back the iron door. I jumped for it,

but was too late, for the cord ran like lightning through the pulley-block, and

the heavy mass fell forward from its own weight.

As the door closed I

caught a glimpse of our poor companion’s face. He seemed frozen with terror.

His eyes stared with a horrible anguish as if dazed, and no sound came from his

lips.

And then the spikes did

their work. Happily the end was quick, for when I wrenched open the door they

had pierced so deep that they had locked in the bones of the skull through

which they had crushed, and actually tore him—it—out of his iron prison till,

bound as he was, he fell at full length with a sickly thud upon the floor, the

face turning upward as he fell.

I rushed to my wife,

lifted her up and carried her out, for I feared for her very reason if she

should wake from her faint to such a scene. I laid her on the bench outside and

ran back. Leaning against the wooden column was the custodian moaning in pain

whilst he held his reddening handkerchief to his eyes. And sitting on the head

of the poor American was the cat, purring loudly as she licked the blood which

trickled through the gashed socket of his eyes.

I think no one will

call me cruel because I seized one of the old executioner’s swords and shore

her in two as she sat.

Read other great classic horror short stories in this anthology - http://andrewbarger.com/besthorrorshortstories1850.html

#bramstokershortstory #bramstoker #thesquawstory #stokersquaw