Lost Hearts

by

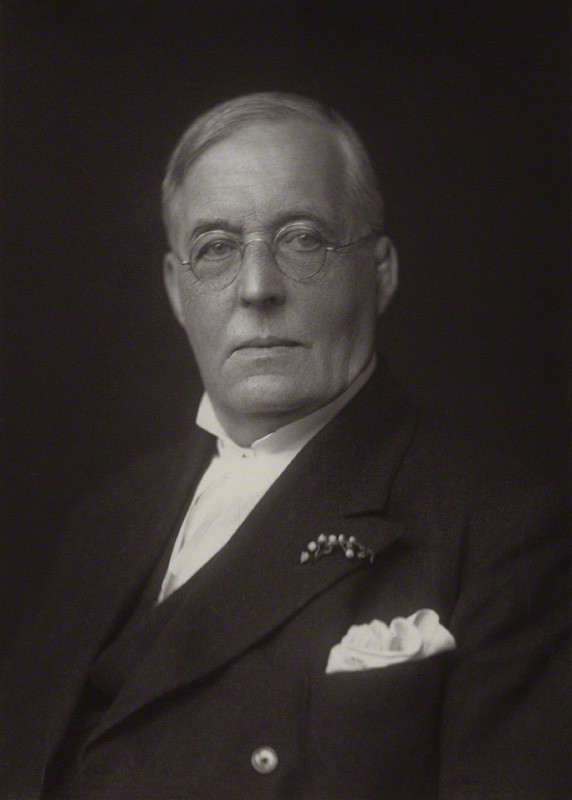

M. R. James

Sacry introduction by http://www.AndrewBarger.com as included in Phantasmal: The Best Ghost Stories 1850-1899

Similar to Ralph Adams Cram in America, M. R. James belonged to the Ivy League of England. He was provost of King’s College, Cambridge for thirteen years and then at Eaton College for eighteen years.

His tenure at those colleges didn’t come until many years after he penned “Lost Hearts” (1895), which is the best ghost story he wrote prior to the turn of the century given its especially fiendish ending and tight writing style. It would later be seem to set the recurring foundation of his later ghost stories.

In his professional life, James was referred to as a “medievalist,” which is a fancy way of saying his scholarly focus was on medieval history. For purposes of constructing a ghost story, his background was a welcome fit as he fashioned many of these stories with a four-legged foundation: (1) a moldering English village as the setting; (2) a protagonist who is a scholar of English history; (3) the protagonist comes across an ancient secret in an old manuscript or historical artifact; and (4) a ghostly creature is reanimated as a result.

The formula worked quiet well for James. Four collections of his popular ghost and supernatural stories were published during his lifetime: Ghost Stories of an Antiquary (1904), More Ghost Stories of an Antiquary (1911), A Thin Ghost and Others (1919), and A Warning to the Curious and Other Ghost Stories (1925).

“Lost Hearts” was found in the earliest collection before the cares and reserve of the universities overtook him. It was first published in the December 1895 issue of the venerable Pall Mall Magazine, [“Lost Hearts,” M. R. James, Pall Mall Magazine, 1895, pgs. 639-47] which published original stories from luminaries such as Joseph Conrad, Jack London, and Rudyard Kipling.

Montague Summers called “Lost Hearts” one of James’s “best stories” while he deemed James to be “among the greatest . . . of modern exponents of the supernatural in fiction.” [The Supernatural Omnibus: Being a Collection of Stories of Apparitions, Witchcraft, Werewolves, Diabolism, Necromancy, Satanism, Divination, Sorcery, Goety, Voodo, Possession, Occult, Doom and Destiny, Montague Summers, 1931, pg. 1]

LOST HEARTS

1895

IT WAS, AS far as I can ascertain, in September of the year 1811 that a postchaise [An enclosed horse-drawn carriage having four wheels] drew up before the door of Aswarby Hall, [Large English country house demolished in 1951 due to military occupation after World War II and owned through the years by the Hervey, Carres, and Whichcote families, “Aswarby Hall,” Lincstothepast.com, 2016] in the heart of Lincolnshire. [Rural farming county with Aswarby parish that had only 142 residents during 1891, which is 4 years before “Lost Hearts” was published, and three farms; Kelly’s Directory of Lincolnshire with the Port of Hull and Neighborhood, E. R. Kelly, 1885, pg. 674]

The little boy who was the only passenger in the chaise, and who jumped out as soon as it had stopped, looked about him with the keenest curiosity during the short interval that elapsed between the ringing of the bell and the opening of the hall door.

He saw a tall, square, red-brick house, built in the reign of Anne; [Queen Anne (1665-1714) ruled over Great Britain from 1707-1714] a stone-pillared porch had been added in the purer classical style of 1790; [Porch on a flat roof of the house] the windows of the house were many, tall and narrow, with small panes and thick white woodwork. A pediment, pierced with a round window, crowned the front. There were wings to right and left, connected by curious glazed galleries, supported by colonnades, with the central block. These wings plainly contained the stables and offices of the house. Each was surmounted by an ornamental cupola with a gilded vane. [Weather vane]

An evening light shone on the building, making the window-panes glow like so many fires. Away from the Hall in front stretched a flat park studded with oaks and fringed with firs, which stood out against the sky. The clock in the church-tower, buried in trees on the edge of the park, only its golden weathercock catching the light, was striking six, and the sound came gently beating down the wind. It was altogether a pleasant impression, though tinged with the sort of melancholy appropriate to an evening in early autumn, that was conveyed to the mind of the boy who was standing in the porch waiting for the door to open to him.

He had just come from Warwickshire, and some six months ago had been left an orphan. Now, owing to the generous and unexpected offer of his elderly cousin, Mr. Abney, he had come to live at Aswarby. The offer was unexpected, because all who knew anything of Mr. Abney looked upon him as a somewhat austere recluse, into whose steady-going household the advent of a small boy would import a new and, it seemed, incongruous element. The truth is that very little was known of Mr. Abney’s pursuits or temper.

The Professor of Greek at Cambridge had been heard to say that no one knew more of the religious beliefs of the later pagans than did the owner of Aswarby. Certainly his library contained all the then available books bearing on the Mysteries, [Likely a reference to the Eleusinian Mysteries, which consisted of secret religious rites performed by various cults] the Orphic poems, [In Greek mythology Orpheus traveled to Hell and returned with religious hymns and poems] the worship of Mithras, [Secret religions of the ancient Romans that focused on the deity Mithras] and the Neo-Platonists. [Formed a belief in using spiritualism to enhance the soul]

In the marble-paved hall stood a fine group of Mithras slaying a bull, which had been imported from the Levant [Vast area of Arabic, Greek and Turkish speaking countries in the eastern Mediterranean] at great expense by the owner. He had contributed a description of it to the Gentleman’s Magazine, [A London magazine founded in 1731 that published news and literary articles for nearly 200 years] and he had written a remarkable series of articles in the Critical Museum [A made-up magazine] on the superstitions of the Romans of the Lower Empire. He was looked upon, in fine, as a man wrapped up in his books, and it was a matter of great surprise among his neighbors that he should ever have heard of his orphan cousin, Stephen Elliott, much more that he should have volunteered to make him an inmate of Aswarby Hall.

Whatever may have been expected by his neighbors, it is certain that Mr. Abney—the tall, the thin, the austere—seemed inclined to give his young cousin a kindly reception. The moment the front-door was opened he darted out of his study, rubbing his hands with delight.

‘How are you, my boy?—how are you? How old are you?’ said he—‘that is, you are not too much tired, I hope, by your journey to eat your supper?’

‘No, thank you, sir,’ said Master Elliott; ‘I am pretty well.’

‘That’s a good lad,’ said Mr. Abney. ‘And how old are you, my boy?’

‘That’s a good lad,’ said Mr. Abney. ‘And how old are you, my boy?’

It seemed a little odd that he should have asked the question twice in the first two minutes of their acquaintance.

‘I’m twelve years old next birthday, sir,’ said Stephen.

‘And when is your birthday, my dear boy? Eleventh of September, eh? That’s well—that’s very well. Nearly a year hence, isn’t it? I like—ha, ha!—I like to get these things down in my book. Sure it’s twelve? Certain?’

‘And when is your birthday, my dear boy? Eleventh of September, eh? That’s well—that’s very well. Nearly a year hence, isn’t it? I like—ha, ha!—I like to get these things down in my book. Sure it’s twelve? Certain?’

‘Yes, quite sure, sir.’

‘Well, well! Take him to Mrs. Bunch’s room, Parkes, and let him have his tea—supper—whatever it is.’

‘Yes, sir,’ answered the staid Mr. Parkes; and conducted Stephen to the lower regions.

Mrs. Bunch was the most comfortable and human person whom Stephen had as yet met in Aswarby. She made him completely at home; they were great friends in a quarter of an hour: and great friends they remained. Mrs. Bunch had been born in the neighborhood some fifty-five years before the date of Stephen’s arrival, and her residence at the Hall was of twenty years’ standing. Consequently, if anyone knew the ins and outs of the house and the district, Mrs. Bunch knew them; and she was by no means disinclined to communicate her information.

Certainly there were plenty of things about the Hall and the Hall gardens which Stephen, who was of an adventurous and inquiring turn, was anxious to have explained to him. ‘Who built the temple at the end of the laurel walk? Who was the old man whose picture hung on the staircase, sitting at a table, with a skull under his hand?’

These and many similar points were cleared up by the resources of Mrs. Bunch’s powerful intellect. There were others, however, of which the explanations furnished were less satisfactory.

These and many similar points were cleared up by the resources of Mrs. Bunch’s powerful intellect. There were others, however, of which the explanations furnished were less satisfactory.

One November evening Stephen was sitting by the fire in the housekeeper’s room reflecting on his surroundings.

‘Is Mr. Abney a good man, and will he go to heaven?’ he suddenly asked, with the peculiar confidence which children possess in the ability of their elders to settle these questions, the decision of which is believed to be reserved for other tribunals.

‘Good?—bless the child!’ said Mrs. Bunch. ‘Master’s as kind a soul as ever I see! Didn’t I never tell you of the little boy as he took in out of the street, as you may say, this seven years back? and the little girl, two years after I first come here?’

‘No. Do tell me all about them, Mrs. Bunch—now this minute!’

‘Well,’ said Mrs. Bunch, ‘the little girl I don’t seem to recollect so much about. I know master brought her back with him from his walk one day, and give orders to Mrs. Ellis, as was housekeeper then, as she should be took every care with. And the pore child hadn’t no one belonging to her—she telled me so her own self—and here she lived with us a matter of three weeks it might be; and then, whether she were somethink of a gipsy in her blood or what not, but one morning she out of her bed afore any of us had opened a eye and neither track nor yet trace of her have I set eyes on since. Master was wonderful put about, and had all the ponds dragged; but it’s my belief she was had away by them gipsies, for there was singing round the house for as much as an hour the night she went, and Parkes, he declare as he heard them a-calling in the woods all that afternoon. Dear, dear! a hodd child she was, so silent in her ways and all, but I was wonderful taken up with her, so domesticated she was—surprising.’

‘And what about the little boy?’ said Stephen.

‘Ah, that pore boy!’ sighed Mrs. Bunch. ‘He were a foreigner—Jevanny he called hisself—and he come a-tweaking his ‘urdy-gurdy [Hurdy-gurdy is a small stringed folk instrument] round and about the drive one winter day, and master ‘ad him in that minute, and ast all about where he came from, and how old he was, and how he made his way, and where was his relatives, and all as kind as heart could wish. But it went the same way with him. They’re a hunruly lot, them foreign nations, I do suppose, and he was off one fine morning just the same as the girl. Why he went and what he done was our question for as much as a year after; for he never took his ‘urdy-gurdy, and there it lays on the shelf.’

The remainder of the evening was spent by Stephen in miscellaneous cross-examination of Mrs. Bunch and in efforts to extract a tune from the hurdy-gurdy.

That night he had a curious dream. At the end of the passage at the top of the house, in which his bedroom was situated, there was an old disused bathroom. It was kept locked, but the upper half of the door was glazed, and, since the muslin curtains which used to hang there had long been gone, you could look in and see the lead-lined bath affixed to the wall on the right hand, with its head towards the window.

On the night of which I am speaking, Stephen Elliott found himself, as he thought, looking through the glazed door. The moon was shining through the window, and he was gazing at a figure which lay in the bath.

His description of what he saw reminds me of what I once beheld myself in the famous vaults of St. Michan’s Church in Dublin, which possess the horrid property of preserving corpses from decay for centuries. [Gothic church in Ireland containing underground crypts with remains mummified by the natural limestone deposits in the earth, both M. R. James and Bram Stoker are believed to have visited the crypts] A figure inexpressibly thin and pathetic, of a dusty leaden color, enveloped in a shroud-like garment, the thin lips crooked into a faint and dreadful smile, the hands pressed tightly over the region of the heart.

As he looked upon it, a distant, almost inaudible moan seemed to issue from its lips, and the arms began to stir. The terror of the sight forced Stephen backwards, and he awoke to the fact that he was indeed standing on the cold boarded floor of the passage in the full light of the moon. With a courage which I do not think can be common among boys of his age, he went to the door of the bathroom to ascertain if the figure of his dream were really there. It was not, and he went back to bed.

Mrs. Bunch was much impressed next morning by his story, and went so far as to replace the muslin curtain over the glazed door of the bathroom. Mr. Abney, moreover, to whom he confided his experiences at breakfast, was greatly interested, and made notes of the matter in what he called ‘his book.’

The spring equinox was approaching, as Mr. Abney frequently reminded his cousin, adding that this had been always considered by the ancients to be a critical time for the young: that Stephen would do well to take care of himself, and to shut his bedroom window at night; and that Censorinus had some valuable remarks on the subject. [Censorinus was a Roman historian and grammarian whose text De Die Natale speaks of all durations of time] Two incidents that occurred about this time made an impression upon Stephen’s mind.

The first was after an unusually uneasy and oppressed night that he had passed—though he could not recall any particular dream that he had had.

The following evening Mrs. Bunch was occupying herself in mending his nightgown.

‘Gracious me, Master Stephen!’ she broke forth rather irritably, ‘how do you manage to tear your nightdress all to flinders this way? Look here, sir, what trouble you do give to poor servants that have to darn and mend after you!’

There was indeed a most destructive and apparently wanton series of slits or scorings in the garment, which would undoubtedly require a skillful needle to make good. They were confined to the left side of the chest—long, parallel slits, about six inches in length, some of them not quite piercing the texture of the linen. Stephen could only express his entire ignorance of their origin: he was sure they were not there the night before.

‘But,’ he said, ‘Mrs. Bunch, they are just the same as the scratches on the outside of my bedroom door; and I’m sure I never had anything to do with making them?’

Mrs. Bunch gazed at him open-mouthed, then snatched up a candle, departed hastily from the room, and was heard making her way upstairs. In a few minutes she came down.

‘Well,’ she said, ‘Master Stephen, it’s a funny thing to me how them marks and scratches can ‘a’ come there—too high up for any cat or dog to ‘ave made ‘em, much less a rat: for all the world like a Chinaman’s fingernails, as my uncle in the tea-trade used to tell us of when we was girls together. I wouldn’t say nothing to master, not if I was you, Master Stephen, my dear; and just turn the key of the door when you go to your bed.’

‘I always do, Mrs. Bunch, as soon as I’ve said my prayers.’

‘Ah, that’s a good child: always say your prayers, and then no one can’t hurt you.’

Herewith Mrs. Bunch addressed herself to mending the injured nightgown, with intervals of meditation, until bedtime. This was on a Friday night in March, 1812. [The second Friday in March of 1812 was Friday the 13th in the Gregorian calendar]

On the following evening the usual duet of Stephen and Mrs. Bunch was augmented by the sudden arrival of Mr. Parkes, the butler, who as a rule kept himself rather to himself in his own pantry. He did not see that Stephen was there: he was, moreover, flustered and less slow of speech than was his wont.

‘Master may get up his own wine, if he likes, of an evening,’ was his first remark. ‘Either I do it in the daytime or not at all, Mrs. Bunch. I don’t know what it may be: very like it’s the rats, or the wind got into the cellars; but I’m not so young as I was, and I can’t go through with it as I have done.’

‘Well, Mr. Parkes, you know it is a surprising place for the rats, is the Hall.’

‘I’m not denying that, Mrs. Bunch; and, to be sure, many a time I’ve heard the tale from the men in the shipyards about the rat that could speak. I never laid no confidence in that before; but tonight, if I’d demeaned myself to lay my ear to the door of the further bin, I could pretty much have heard what they was saying.’

‘Oh, there, Mr. Parkes, I’ve no patience with your fancies! Rats talking in the wine-cellar indeed!’

‘Well, Mrs. Bunch, I’ve no wish to argue with you: all I say is, if you choose to go to the far bin, and lay your ear to the door, you may prove my words this minute.’

‘What nonsense you do talk, Mr. Parkes —not fit for children to listen to! Why, you’ll be frightening Master Stephen there out of his wits.’

‘What! Master Stephen?’ said Parkes, awaking to the consciousness of the boy’s presence. ‘Master Stephen knows well enough when I’m a-playing a joke with you, Mrs. Bunch.’

In fact, Master Stephen knew much too well to suppose that Mr. Parkes had in the first instance intended a joke. He was interested, not altogether pleasantly, in the situation; but all his questions were unsuccessful in inducing the butler to give any more detailed account of his experiences in the wine-cellar.

We have now arrived at March 24, 1812. [Under the Julian calendar March 24th is the 365th and last day of the year, which was first adopted by England in the 12th century A.D. and was replaced by the Gregorian calendar in 1752] It was a day of curious experiences for Stephen: a windy, noisy day, which filled the house and the gardens with a restless impression. As Stephen stood by the fence of the grounds, and looked out into the park, he felt as if an endless procession of unseen people were sweeping past him on the wind, borne on resistlessly and aimlessly, vainly striving to stop themselves, to catch at something that might arrest their flight and bring them once again into contact with the living world of which they had formed a part. After luncheon that day Mr. Abney said:

‘Stephen, my boy, do you think you could manage to come to me tonight as late as eleven o’clock in my study? I shall be busy until that time, and I wish to show you something connected with your future life which it is most important that you should know. You are not to mention this matter to Mrs. Bunch nor to anyone else in the house; and you had better go to your room at the usual time.’

Here was a new excitement added to life: Stephen eagerly grasped at the opportunity of sitting up till eleven o’clock. He looked in at the library door on his way upstairs that evening, and saw a brazier, [Portable metallic heater in which lighted wood or coals were placed] which he had often noticed in the corner of the room, moved out before the fire; an old silver-gilt cup stood on the table, filled with red wine, and some written sheets of paper lay near it. Mr. Abney was sprinkling some incense on the brazier from a round silver box as Stephen passed, but did not seem to notice his step.

The wind had fallen, and there was a still night and a full moon. At about ten o’clock Stephen was standing at the open window of his bedroom, looking out over the country. Still as the night was, the mysterious population of the distant moonlit woods was not yet lulled to rest. From time to time strange cries as of lost and despairing wanderers sounded from across the mere. They might be the notes of owls or water-birds, yet they did not quite resemble either sound. Were not they coming nearer?

Now they sounded from the nearer side of the water, and in a few moments they seemed to be floating about among the shrubberies. Then they ceased; but just as Stephen was thinking of shutting the window and resuming his reading of Robinson Crusoe, he caught sight of two figures standing on the gravelled terrace that ran along the garden side of the Hall—the figures of a boy and girl, as it seemed; they stood side by side, looking up at the windows. Something in the form of the girl recalled irresistibly his dream of the figure in the bath. The boy inspired him with more acute fear.

Whilst the girl stood still, half smiling, with her hands clasped over her heart, the boy, a thin shape, with black hair and ragged clothing, raised his arms in the air with an appearance of menace and of unappeasable hunger and longing. The moon shone upon his almost transparent hands, and Stephen saw that the nails were fearfully long and that the light shone through them. As he stood with his arms thus raised, he disclosed a terrifying spectacle. On the left side of his chest there opened a black and gaping rent; and there fell upon Stephen’s brain, rather than upon his ear, the impression of one of those hungry and desolate cries that he had heard resounding over the woods of Aswarby all that evening. In another moment this dreadful pair had moved swiftly and noiselessly over the dry gravel, and he saw them no more.

Inexpressibly frightened as he was, he determined to take his candle and go down to Mr. Abney’s study, for the hour appointed for their meeting was near at hand. The study or library opened out of the front-hall on one side, and Stephen, urged on by his terrors, did not take long in getting there. To effect an entrance was not so easy. It was not locked, he felt sure, for the key was on the outside of the door as usual. His repeated knocks produced no answer. Mr. Abney was engaged: he was speaking. What! why did he try to cry out? and why was the cry choked in his throat? Had he, too, seen the mysterious children? But now everything was quiet, and the door yielded to Stephen’s terrified and frantic pushing.

*****

On the table in Mr. Abney’s study certain papers were found which explained the situation to Stephen Elliott when he was of an age to understand them. The most important sentences were as follows:

‘It was a belief very strongly and generally held by the ancients—of whose wisdom in these matters I have had such experience as induces me to place confidence in their assertions—that by enacting certain processes, which to us moderns have something of a barbaric complexion, a very remarkable enlightenment of the spiritual faculties in man may be attained: that, for example, by absorbing the personalities of a certain number of his fellow-creatures, an individual may gain a complete ascendancy over those orders of spiritual beings which control the elemental forces of our universe.

‘It is recorded of Simon Magus [A Samaritan religious figure reported to have sorcerylike powers of levitation in the Acts of Peter and the Acts of Peter and Paul of the Biblical apocrypha] that he was able to fly in the air, to become invisible, or to assume any form he pleased, by the agency of the soul of a boy whom, to use the libelous phrase employed by the author of the Clementine Recognitions, he had “murdered.” [Reference to the anonymous author of the Clementine Recognitions and Homilies whose date of authorship is also unknown] I find it set down, moreover, with considerable detail in the writings of Hermes Trismegistus, [Fictitious Greek author of the Hermetic Corpus texts that tell of sorcery] that similar happy results may be produced by the absorption of the hearts of not less than three human beings below the age of twenty-one years. To the testing of the truth of this receipt I have devoted the greater part of the last twenty years, selecting as the corpora vilia [Person suitable only for experimentation or for the particular experiment] of my experiment such persons as could conveniently be removed without occasioning a sensible gap in society. The first step I effected by the removal of one Phoebe Stanley, a girl of gipsy extraction, on March 24, 1792. The second, by the removal of a wandering Italian lad, named Giovanni Paoli, on the night of March 23, 1805. [Night of full moon in old calendars] The final “victim”—to employ a word repugnant in the highest degree to my feelings—must be my cousin, Stephen Elliott. His day must be this March 24, 1812.

‘It was a belief very strongly and generally held by the ancients—of whose wisdom in these matters I have had such experience as induces me to place confidence in their assertions—that by enacting certain processes, which to us moderns have something of a barbaric complexion, a very remarkable enlightenment of the spiritual faculties in man may be attained: that, for example, by absorbing the personalities of a certain number of his fellow-creatures, an individual may gain a complete ascendancy over those orders of spiritual beings which control the elemental forces of our universe.

‘It is recorded of Simon Magus [A Samaritan religious figure reported to have sorcerylike powers of levitation in the Acts of Peter and the Acts of Peter and Paul of the Biblical apocrypha] that he was able to fly in the air, to become invisible, or to assume any form he pleased, by the agency of the soul of a boy whom, to use the libelous phrase employed by the author of the Clementine Recognitions, he had “murdered.” [Reference to the anonymous author of the Clementine Recognitions and Homilies whose date of authorship is also unknown] I find it set down, moreover, with considerable detail in the writings of Hermes Trismegistus, [Fictitious Greek author of the Hermetic Corpus texts that tell of sorcery] that similar happy results may be produced by the absorption of the hearts of not less than three human beings below the age of twenty-one years. To the testing of the truth of this receipt I have devoted the greater part of the last twenty years, selecting as the corpora vilia [Person suitable only for experimentation or for the particular experiment] of my experiment such persons as could conveniently be removed without occasioning a sensible gap in society. The first step I effected by the removal of one Phoebe Stanley, a girl of gipsy extraction, on March 24, 1792. The second, by the removal of a wandering Italian lad, named Giovanni Paoli, on the night of March 23, 1805. [Night of full moon in old calendars] The final “victim”—to employ a word repugnant in the highest degree to my feelings—must be my cousin, Stephen Elliott. His day must be this March 24, 1812.

‘The best means of effecting the required absorption is to remove the heart from the living subject, to reduce it to ashes, and to mingle them with about a pint of some red wine, preferably port. The remains of the first two subjects, at least, it will be well to conceal: a disused bathroom or wine-cellar will be found convenient for such a purpose. Some annoyance may be experienced from the psychic portion of the subjects, which popular language dignifies with the name of ghosts. But the man of philosophic temperament—to whom alone the experiment is appropriate— will be little prone to attach importance to the feeble efforts of these beings to wreak their vengeance on him. I contemplate with the liveliest satisfaction the enlarged and emancipated existence which the experiment, if successful, will confer on me; not only placing me beyond the reach of human justice (so called), but eliminating to a great extent the prospect of death itself.’

*****

Mr. Abney was found in his chair, his head thrown back, his face stamped with an expression of rage, fright, and mortal pain. In his left side was a terrible lacerated wound, exposing the heart. There was no blood on his hands, and a long knife that lay on the table was perfectly clean. A savage wild-cat might have inflicted the injuries. The window of the study was open, and it was the opinion of the coroner that Mr. Abney had met his death by the agency of some wild creature.

But Stephen Elliott’s study of the papers I have quoted led him to a very different conclusion.